The First Time…

Stories matter. They are the center of our identity and our way of engaging with ourselves and the world. Owning one's story and sharing it with others is an act of bravery and a sacred offering. What we release and give to the world comes back to us in the form of healing and connection, offering hope and optimism in the face of shared adversity.

I was born and raised in Waukegan, a town on the shores of Lake Michigan, just outside Chicago, IL.

My mom and dad, James and Myrtle White, were very bohemian in their thinking. They valued culture, the arts, and education. My father, who I am named after, was a lover of literature and music, and for 40 years, he worked as a concert producer. I spent a lot of time in my childhood behind the stage of music shows, enjoying an up close and personal view of musicians and their crew. My mother, a music lover and a singer, was graceful and elegant. Kind and soft-spoken, she was a health food nut and served us vegan and vegetarian meals. Together, my parents worked full-time to give my sister and me the best advantages.

Because they valued education, our family lived on the side of town where the public schools were thriving and strong. We lived in the only apartment building in the neighborhood, a two-bedroom unit on the second floor. Beyond the three-story concrete lay miles of tree-lined streets with manicured lawns, two-story colonials, and a yacht club nearby on the lakefront. The difference between my home and the homes of the children in my neighborhood was vast. The poverty of my apartment building was singular, and so was our family's skin color.

When referring to crossing cultural borders, we often use the term code-switching. Code-switching is a skill we all develop early in life to navigate new and different environments. It takes time to learn, and children who do not master this skill can be vulnerable to the stigma of being different.

Never was this truer than when my mother enrolled me in Happy Day Nursery's preschool program at the age of five. What I recall most were the teachers: towering, looming figures with stern voices and cold eyes.

I also recall meeting my very first white friend. Her name was Cicely. Cicely had brunette hair and catlike, feline features. She had mischievous eyes, a wide toothy grin, and was prone to fits of hysterical laughter.

As a routine, our pre-k class returned from recess to a calm, dark classroom where the cots were laid out for afternoon nap time. One afternoon, the students charged inside and waited in line to use the bathroom before nap time. Cicely and I, the last to come inside, joined the end of the line. One by one, the boys and girls exited the bathroom and settled into their cots to fight sleep, their eyes gazing blearily at the dwindling line of students in front of the bathroom door.

When our turn came, Cicely and I decided to go inside together. Needing to go to the bathroom badly, I wriggled in discomfort as Cicely went first. Once she finished, I rushed to sit on the toilet, heaving a contented sigh of relief as my head fell into my lap. But when I lifted my head again, Cicely gave me a sly, knowing half grin, opened the bathroom door widely, and strolled towards her cot with a slow, self-satisfied strut.

My eyes widened in horror as my classmates glared at me on the toilet, and all I could do was yell, "Hey Cicely, come back, close the door, close the door…."

As she continued to sachet, I heard a looming adult voice, angry and loud. At first, and with much relief, I thought she was reprimanding Cicely, ordering her back to close the door. But upon pause, I realized the teacher's angry voice was directed at me. "Jamie, you are playing around and keeping everyone from resting… get quiet and get out of the bathroom now."

All I could do was comply, and the shame and humiliation of having to stand up and dress before my classmates never left me.

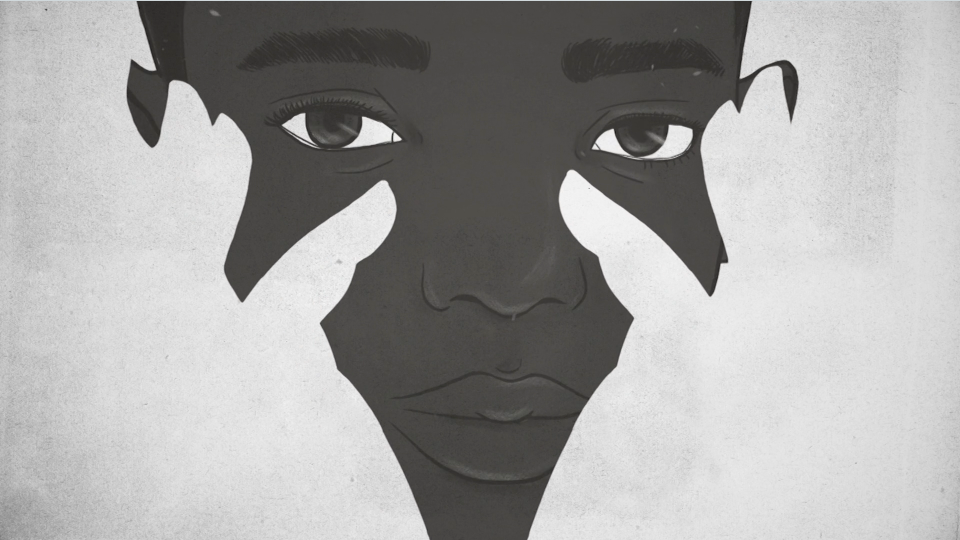

Now, I cannot say with any level of certainty how that teacher saw me, what she felt about me, why she treated me so insensitively, but I do know how it made me feel: like the color of my skin somehow, someway, had something to do with it. It was the first time I realized I was black.

I am not the only person who, at an early age, has felt aware of their differences. W.E.B. Debois famously writes about this experience in The Souls of Black Folks. In 2017, CNN interviewed dozens of celebrities, news anchors, journalists, and others to describe the moment when they first realized that being black affected how people treated them. CNN's docuseries sparked a nationwide conversation. Hundreds of people of all ethnicities took to their cameras to relay the moment they realized their differences.

In her intimate memoir, The Year of Yes, Shonda Rhimes, writer and creator of T.V. shows like Grey's Anatomy, Scandal, and How to Get Away with Murder, coined this universal experience F.O.D.: First, Only, Different. No matter one's culture, ethnicity, or life experience, we have all, at some point in time, experienced this otherness in a way that shaped us and informed our sense of self-worth. As an educator, I hold onto my story and offer it to students. I consider it an honor to share because my story offers students an opportunity to release their own story along with all its false implications, allowing them to hold on only to parts that make them stronger, wiser, and more capable of navigating the world.

When was the first time you felt your own separateness? Have you released it, gifted your story to the world? If not, what are you waiting for? We could all use a dose of the wisdom you have to share.